Telecommunications History Group Resources

931 14th St. Historic Building

Trains & Telegraphs - Local Communications History

In 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse perfected the electromagnetic telegraph, and within 10 years the telegraph was seen as the scientific marvel that would bridge the communications gap between California and the rest of the country. By 1860, forces were in motion to construct a line across the continent to connect New York with San Francisco and all major points between. In 1861, Congress passed the Pacific Telegraph Act authorizing a subsidy in the form of a loan of $40,000 a year for 10 years to any company that would build a telegraph line from the western boundary of Missouri to San Francisco.

In 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse perfected the electromagnetic telegraph, and within 10 years the telegraph was seen as the scientific marvel that would bridge the communications gap between California and the rest of the country. By 1860, forces were in motion to construct a line across the continent to connect New York with San Francisco and all major points between. In 1861, Congress passed the Pacific Telegraph Act authorizing a subsidy in the form of a loan of $40,000 a year for 10 years to any company that would build a telegraph line from the western boundary of Missouri to San Francisco.

For a number of reasons, the Western Union Company bypassed Denver and pushed the line through the South Pass. (A major reason was that the residents of Denver did not fulfill promised stock subscriptions. Another was the ruggedness of the mountains west of Denver.) The western and eastern sections of the transcontinental telegraph line were joined at Salt Lake City on Oct. 24, 1861, on time and under budget. This service met the critical demand for fast communications between the two coasts. The telegraph line operated until May 1869, when it was replaced by a multi-wire system constructed along the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railway lines. The link put an end to the Pony Express, and set the stage for the development of the transcontinental railroad, which would materialize before the end of the decade.

Denver continued to rely on the horse for communication with the outside world until 1863. The Pacific Overland Telegraph Company strung a line from Omaha to San Francisco in 1861. For a time, messages were relayed by horse from Julesburg, as the telegraph lines—like the Pony Express—came only that close to Denver. The first line reached Denver on October 10, 1863. The first message contained congratulations from the mayor of Omaha to Denver Mayor Amos Steck. Rates for ten words were $7.00 to St. Louis, and $9.00 to New York or Boston.

After the initial mining boom, Denver failed to grow and prosper. Leading citizens such as William Byers, of the Rocky Mountain News, and William Gilpin, former territorial governor, began lobbying for a connection to the railroad to pass through Denver.

President Abraham Lincoln appointed John Evans to replace William Gilpin as territorial governor in 1862. Evans was also a commissioner of the Union Pacific Railway, a position he used to Denver’s advantage. (It was Golden, however, that organized Colorado’s first railroad, the Colorado Central, in 1864.)

Once again, Denver’s proximity to the rugged Rockies worked against it. The engineers of the Union Pacific railroad decided that a route through Wyoming would be much faster and cheaper to build than one through Denver. The transcontinental railroad bypassed Denver in favor of Cheyenne and the gentler hills of Wyoming. Denver’s population decreased as pioneers moved closer to what they thought would become the new rail hub. Byers and Evans grew alarmed, and joined with bankers David Moffat and Luther and Charles Kountze, and entrepreneur Walter Scott Cheesman to revitalize the effort to obtain a railroad presence in the region.

Once again, Denver’s proximity to the rugged Rockies worked against it. The engineers of the Union Pacific railroad decided that a route through Wyoming would be much faster and cheaper to build than one through Denver. The transcontinental railroad bypassed Denver in favor of Cheyenne and the gentler hills of Wyoming. Denver’s population decreased as pioneers moved closer to what they thought would become the new rail hub. Byers and Evans grew alarmed, and joined with bankers David Moffat and Luther and Charles Kountze, and entrepreneur Walter Scott Cheesman to revitalize the effort to obtain a railroad presence in the region.

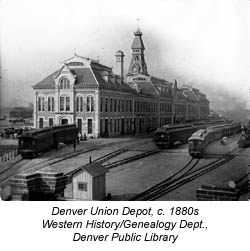

Evans, Byers and the Board of Trade persuaded voters to approve bond support for and donate the labor to build the Denver Pacific Railroad between Denver and Cheyenne, and it was completed on June 24, 1870. Soon other railroads built to Denver, and it became the rail hub of the Rockies. By 1900, a hundred trains a day moved in and out of Denver’s Union Station.

More information on the telegraph and its development can be found in the Virtual Museum’s A Time Before Phones article. More about the transcontinental telegraph can be seen at the Engineering and Technology History Wiki: http://ethw.org/Telegraph