Telecommunications History Group Resources

931 14th St. Historic Building

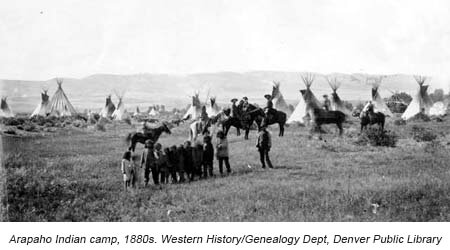

Arapaho Indians & Prairie Schooners - Building Site History

The Arapaho were part of the Algonquin family, from the Great Lakes area. As European settlers moved west, other tribes moved into the Arapaho’s homeland, causing them to move further west. The Northern Arapaho ended up in what is now Wyoming, the Southern Arapaho in Colorado. When they reached the Rocky Mountains (about 1750), they encountered Colorado Indians, including the Utes, who would not allow them access to the mountains. So the Southern Arapaho settled in the South Platte River Valley.

The Arapaho were part of the Algonquin family, from the Great Lakes area. As European settlers moved west, other tribes moved into the Arapaho’s homeland, causing them to move further west. The Northern Arapaho ended up in what is now Wyoming, the Southern Arapaho in Colorado. When they reached the Rocky Mountains (about 1750), they encountered Colorado Indians, including the Utes, who would not allow them access to the mountains. So the Southern Arapaho settled in the South Platte River Valley.

They weren’t a very large tribe, so they developed a strategy of peaceful coexistence with their neighbors, the Sioux and the Cheyenne. They also were friendly to traders and trappers. By 1850, up to 1,500 Arapaho were camped near the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. The extensive camp included the land where the 931 14th St. building now stands. The Arapaho (and their allies the Southern Cheyenne) were promised the territory between the Platte and the Arkansas rivers at the eastern base of the Rockies.

Seven years later gold was discovered in the sands of Cherry Creek and the South Platte. The gold seekers were greeted by friendly Indians, who (because of their dealings with fur traders) were able to speak both French and English. Arapaho chief Little Raven entertained newcomers in his handsomely decorated tipi and visited with them in their own houses. It was a short honeymoon.

The Arapaho soon grew tired of their aggressive guests, and the whites thought the Indians should leave the newly-founded city of Denver. The Fort Wise Treaty of 1861 expelled the Arapaho from their homeland in the Cherry Creek and South Platte valley and confined them to a much smaller, more arid area of southeastern Colorado north of the Arkansas River–near a stream called Sand Creek. Many Arapaho chiefs refused to sign the treaty, and others later claimed they were tricked into signing the treaty that brought them to what they called “no water land.” On November 29, 1864, more than 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho, two-thirds of them women and children, were killed in what has become known as the Sand Creek Massacre. But the die had been cast, and the settlers were there to stay.